Creating en effective post-discharge program from customer journey mapping

The very first version of our post-discharge program started on one floor of one hospital inside a large health system. It was small, contained, and had the potential to grow into something much bigger if we could make it work.

But this was a brand new service for us. We were supporting a higher-acuity population, navigating unfamiliar workflows, and rolling out a program we hadn’t fully defined or validated yet.

We were learning in real time. Some ideas landed, others fell flat, and my job was to make sure we learned quickly and kept testing new approaches until we built something that actually worked… something with strong engagement and lower readmission risk.

But the early signals weren’t strong. Our referral-to-enrollment conversion hovered around 30%, which isn’t terrible, but also isn’t great. And for those who did enroll, engagement dropped off quickly. Calls went unanswered, and many people ghosted us after the first week or even after the first call.

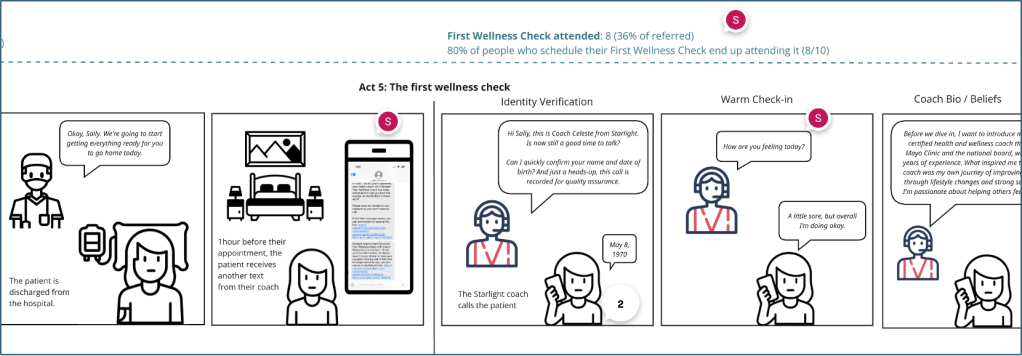

Something deeper wasn’t working, and I needed to understand why. So I built a customer journey map.

The process behind the map

I needed to see the full picture… every step, every message, every moment of confusion or friction.

I started with the raw material: real call transcripts, coach notes, and message threads. I ran transcripts through Gemini to surface recurring themes and tone patterns, and I spoke with the people living inside the workflow every day to understand what the experience really felt like for patients.

I placed real quotes directly onto the map. If a phrase felt awkward on the map, it was probably awkward on the phone. That small detail ended up revealing some of the biggest gaps in how we were showing up.

And because I wanted to capture the truth of the journey, I didn’t stop at patient-facing interactions. I mapped backend workflows, timing delays, internal handoffs, and all the invisible moments between teams. It became a quasi service-design blueprint… not just what patients heard, but everything happening around them.

Once the full experience was visualized, the patterns became impossible to ignore.

What the map revealed

The insights we gathered from this process were invaluable, and an unexpected bonus was the conversations the map sparked.

It brought together voices that rarely share space to collaborate. Coaches opened up about what worked and what didn’t. Coordinators explained where handoffs broke down. Leadership could finally contextualize the friction points they had seen in the metrics. And patients added emotional context we never would have captured from data alone.

Patterns emerged that went beyond operations. Our messaging wasn’t landing the way we thought. We were placing staff in roles that didn’t fully match their scope. Certain workflows felt heavier than they needed to be. Some steps added friction instead of clarity. And pieces of the program that we believed were genuinely helpful turned out to be confusing or redundant once we saw them through the patient’s eyes.

How we used it

As we studied the map together, it became more than a research artifact. It became a shared language.

We used it to tighten how we communicate, simplify our scripts, adjust our timing, and ground our message in what patients truly need in the first 30 days after a hospitalization. Instead of building solutions in isolation, we co-created them with the people closest to the work.

Because the map was visual, simple, and filled with real quotes, it also became a training tool. New staff could instantly understand not only what to do, but why it mattered, and how it felt to the patient on the other end of the line.

The map aligned teams and helped us solve problems with a shared understanding instead of siloed assumptions.

How it helped me become a better leader

What began as a design exercise ended up changing how I lead.

It pulled me back into real conversations with patients and with the people doing the work every day. It reminded me that alignment comes from visibility, not process. And it made me feel more connected to our staff, our patients, and the heart of the program we were trying to build.

The map helped break down silos and rebuild trust. It gave every team a shared picture of how everything fits together. And in the middle of building it, I realized it was making me a better leader… because I felt more aligned with teams, relationships were strengthened, and we had real buy-in across the company for the changes we needed to make.

Lessons learned

If you want to improve a pilot program, the best place to start is by mapping the end-to-end experience. It gives you clarity fast and helps everyone see the same problems, the same friction points, and the same opportunities.

Here are a few things I learned along the way:

- Map the current state so you can make small, incremental changes the care team can follow, instead of jumping straight to a perfect future-state program that no one is ready to operate.

- When mapping conversations, use real quotes from transcripts whenever you can. If they sound awkward on the map, they’ll sound awkward in real life.

- Include every touchpoint across every team and get everyone’s perspective, because that’s where the real gaps and insights tend to live.

- Combine the journey map with quantitative data, like funnel conversion metrics, to validate patterns and size the problems you’re seeing. It will show you where to start.

- Have as many people as possible review and share feedback on the map, even if they aren’t directly contributing to the experience, because fresh perspectives often surface opportunities you wouldn’t have considered.

- Listen to your team the same way you listen to your customers/patients.

What began as a simple mapping exercise turned into a shared reference point for the whole company. It helped us see the patient experience clearly and improve it as one team. And somewhere in the process, I was reminded that leadership and design both depend on the same things… curiosity, empathy, and a grounded view of what’s real.